Chichubamba—What fascinates me is that no-one died. One night in October, 2010, An avalanche came roaring down the valley below the Apu chichon glacier, pictured above, heading directly toward this agrotourism community on the border of Urubamba. Someone lucky enough not to be in the line of fire had a telephone handy and notified the people downstream. And into their streets they ran, racing from house to house, telling their neighbors to flee. The avalanche worked its way between the hills pictured below down toward the valley where Urubamba is situated.

The straight stretch of road pictured here goes directly uphill into Chichubamba, whose water system was damaged in the slide. Rocks piled up at the edge of the community. But Everyone made it to safety. It proved to be a very effective rescue for a community without a modern emergency infrastructure.

Sometimes news accounts attribute landslides in Peru to earthquakes. But glaciers can also be a cause. In April 2010 a huge ice chunk measuring 500 by 200 meters came off a glacier, and landed in a lake, causing a 23-meter-high tsunami that swept away three people, destroyed a water processing plant serving 60,000 residents, and caused flooding 20 kilometers away

The problem has generated some interesting proposals, including the effort by four men from the village of Licapa to whitewash loose rocks around the summit of one mountain with lime, industrial egg white and water, in hopes of helping the mountain to cool down by reflecting more of the sun’s rays back into space, thereby growing a microclimate for preserving glaciers. They whitewashed two hectares in two weeks. (http://www.markawasi.com/paintmountains.html

When our Global Outreach team from Seattle arrived in Urubamba, a shaman performed a welcoming ceremony in which he called on the spirits of the mountains, the “apus,” to receive and protect us. The rock fall that threatened chichubamba suggests that the apus are not always benevolent spirits.

A few days after our arrival in Urubamba we met Alejondro Huaman Laurel, president of chichubamba, who told us his community filters 45 cubic meters of water each day. Mr. Laurel, pictured below with one of the ProPeru home water filters, took us on a tour of the community’s water system.

We strolled past the small drainage channel through which a steady stream of glacial meltwater flows:

Along the path were walls of rock piled up from the landslide a year earlier:

Clearly visible were water pipes yet to be repaired from the avalanche:

The trees in the background of this photo below are eucalyptus –non-native trees that have been introduced. Most of Peru's native forests are gone, and non-native species which have severely impacted the native ecosystem, have replaced them.

I mentioned that Chichubamba is involved in agrotourism. Cow breeding is a source of income, complemented with textiles, ceramics, the breeding of guinea pigs and beekeeping. Guinea pigs don’t need a lot of help reproducing; when we were installing stoves in people’s homes it was all we could do to keep from stepping on the “cui.” (They call them “cui” because that’s the squeaky sound these critters make as they are scurring around the dirt floors, awaiting the moment when they become the next meal. In a later visit, some of us purchased fresh honey from a local beekeeper, who blew smoke into his hive to calm the little critters and then let members of our group such as Dr. Patty Read-Williams, below, play with the bees.

The folks at Chichubamba are pretty user friendly. After our tour of the waterworks, Mariaelena, a lady whose home was situated near the reservoir, offered Joe Lerman, our translator, fruit from her prickly pear cactus. It was quite sweet and tasty. Then she invied us in to check out her dog, which would willingly suckle a couple kittens living with her.

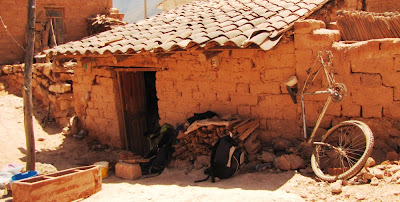

Afterward, Mariaelena posed with her grandson and Global Impact’s Seattle visitors Ena Lee and Amanda Gary. With its dirt floor and gaps between exterior planks, Maria Elena’s home is humble, but she nevertheless is living in a community with a clean, chlorinated drinking water system.

Next: Conclusion of the Inca Diaries—my favorite photos.